The Plunge is a periodic deep-dive into the catalogs of my favorite musicians who have been overlooked, released music under multiple personas or in different styles, or all of the above.

If George Duke were only known for the four songs of his that were repurposed decades hence, he'd have a killer resumé. Thundercat essentially announced his solo-artist existence with a faithful cover of Duke's "For Love (I Come Your Friend)," Daft Punk used his "I Love You More" as the backbone of “Digital Love,” WC and the Maad Circle turned "Reach For It" into a classic g-funk posse cut, and Duke's graceful keyboard on Billy Cobham's "Heather" became the key ingredient of A-Plus' immortal, blissed-out production for Souls of Mischief's "'93 Til Infinity."

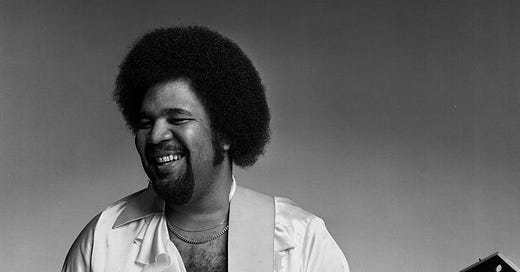

Maybe that is all most people know about Duke, if they know him at all. Or maybe they’ve encountered him as a meme, deploying superhuman funk-patience to play a single note, or drawing out a solo by, yet again, tink-tink-tinking on a lone piano key with Al Jarreau in the cut. While coaxing all manner of weird pitch-bends out of his Mini-Moog and Arp Odyssey, Duke—who could play with earnest feeling as easily as he could also be a complete goofball—eventually became wholly identified with his tailor-made Davis Clavitar keytar (see above) and brandished a self-built, battery-powered lightsaber called the "Dukey Stick" in concert that, according to the man himself, was inspired by Star Wars and (he claimed) was designed by Industrial Light & Magic.

It all makes sense if you remember that the 1970s witnessed the congealing of funk, R&B, prog, and jazz into big new weird shapes that were chops-centric without sacrificing an essential cosmic playfulness. Two of Duke's early musical peers were cool jazz scat-virtuoso Jarreau and electric violinist Jean-Luc Ponty, who sold platinum quantities of space-cadet fusion in the late 1970s. More broadly, Duke counted as contemporaries some of the greatest music ever made: Stevie Wonder’s TONTO era, the Parliament-Funkadelic narrative universe, and Herbie Hancock’s wildly inventive and underrated post-Head Hunters decade. Duke’s collaborators provide more nuanced insight into his entire deal: electric bass virtuoso Stanley Clarke (see above); the Superman Lover himself Johnny “Guitar” Watson; Brazilian fusion vocalist Flora Purim and her percussionist husband Airto Moreira; and linebacker-sized drummer/bandleader Billy Cobham.

It started for Duke in the mid-late 1960s Bay Area scene he fell into while studying at the San Francisco Conservatory Of Music, when the owners of German jazz label SABA (a subsidiary of an electronics manufacturer) offered Duke a contract after seeing him play. Duke’s relative obscurity as an early-1970s solo artist is partially due to his label’s limited American distribution, and perhaps also its marketing of Duke as an ethnographic curiosity that didn’t nearly reflect the hyperactive, future-facing co(s)mic-funk of “Psychocomatic Dung” and “That’s What She Said.”

The early 1970s were also the start of Duke’s incredibly productive career as a collaborator. His label connected Duke with Ponty, and the two cut a couple albums of fiery fusion, with Duke often overshadowed by the novel sight of an electric violinist playing jazz. Duke specifically recalls one momentous performance with Ponty that counted Cannonball Adderley, Frank Zappa, and Quincy Jones as attendees. Soon, Duke hopped on board with Zappa for Chunga’s Revenge and 200 Motels (above), though because Duke wanted to play more jazz than Stockhausen or doo-wop throwback (what Duke called “Fonzie music”), he decamped to Cannonball Adderley’s band for a few years (replacing Joe Zawinul) before coming back to Zappa’s fold. (He’d also play on Jones’ 1973 cover of “You’ve Got It Bad, Girl,” and, six years later, on Off the Wall’s title track.)

Zappa was renowned as an asshole taskmaster, one time singling Duke out on stage, James Brown-style, for a missed cue. “George has made a mistake and he's going to play it for you by himself,” Duke recalls Zappa saying. “So I had to play this piece with a lot of notes in it as a punishment. I never made a mistake again.” But more importantly than honing his chops, Zappa encouraged Duke’s performative side by convincing him to sing, and upped his instrumental repertoire by putting him on to synthesizers—Duke adopted the ARP Odyssey and never looked back.

I first encountered Duke as an undergrad obsessing over Zappa, marveling at Duke traveling the spaceways via "Inca Roads," smearing soul all over "Dickie's Such an Asshole,” tearing up his Rhodes lead on “Eat that Question” and untangling Zappa’s labyrinthine time signatures into a groovy swing session on “Big Swifty.” During Zappa’s epochal run of late 1973 Roxy performances, Duke was easily the most important non-Zappa person on the bandstand. And Zappa returned the favor: listen to the Ernie Isley-style flames that Zappa (anonymously) ignites on Duke’s “Love,” from 1974’s Feel, some of the most soulful fusion-pop this side of “Don’t You Know.” (And then listen to Duke’s solo right after.)

After splitting with Zappa’s band in 1976, Duke signed with Epic/CBS for a run of pop-leaning albums, spurred by Zappa and Stanley Clarke coaxing out Duke’s innate desire to perform. By the time of 1977’s gold-selling Reach For It, Duke had made it on his own terms, with an Earth, Wind, & Fire-influenced form of jazzy Afro-Latin funk-pop that continued across its two successors Don’t Let Go and Follow the Rainbow. By the end of the decade, he’d united numerous music-fan constituencies—his old jazz and Zappa-era fans, his significant Black radio audience, and more than a few prog heads.

Though Duke’s pop relevance declined post-MTV, he never stopped working—he released his final solo album about a month before he passed away in 2013. In the 1980s and 90s, he recorded three albums of slick electro-R&B with Clarke, produced and played the Moog on Deniece Williams’ #1 pop hit “Let’s Hear It For the Boy,” arranged a song for his idol Miles Davis, and remixed Gamble & Huff’s Soul Train theme at Don Cornelius’ request in 1987. Before we wrap up here, just a note that Duke served as Anita Baker’s bandleader and keyboardist during her peak (see below), if you want something to put on after this playlist wraps up.

That said, here’s a playlist of 40 songs that attempt to sum up Duke’s career as a solo artist, collaborator, arranger, and producer (here’s the Apple Music version).

Tracklist:

“For Love (I Come Your Friend) from The Aura Will Prevail (1975)

“We Give Our Love” from Don’t Let Go (1978)

“The Kumquat Kids” from Eddie Henderson, Sunburst (1975)

“That’s What She Said” from I Love the Blues, She Heard My Cry (1975)

“Inca Roads” from Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention, One Size Fits All (1975)

“Almustafa the Beloved” from The Billy Cobham–George Duke Band, Live on Tour in Europe (1976)

“Carry On” from From Me To You (1977)

“Just Family” from Dee Dee Bridgewater, Just Family (1978)

“Straight From The Heart” from Follow the Rainbow (1979)

“From You To Me To You” from Nancy Wilson, This Mother’s Daughter (1976)

“Light As A Feather” from Flora Purim, Butterfly Dreams (1973)

“Back To Where We Never Left” from Liberated Fantasies (1976)

“You’ve Got It Bad Girl” from Quincy Jones, You’ve Got It Bad Girl (1973)

“Love” from Feel (1974)

“Sweet Baby” from Stanley Clarke and George Duke, The Clarke/Duke Project (1981)

“Backyard Ritual” from Miles Davis, Tutu (1986)

“Brazilian Love Affair” from Brazilian Love Affair (1979)

“Eat That Question” from Frank Zappa, The Grand Wazoo (1972)

“King Kong” from Jean-Luc Ponty, King Kong: Jean-Luc Ponty Plays the Music of Frank Zappa (1970)

“I Love You More” from Master of the Game (1979)

“Psychosomatic Dung” from Faces in Reflection (1974)

“Dirty Love” from Frank Zappa/Mothers of Invention, Over-Nite Sensation (1973)

“Let’s Hear It For The Boy” from Deniece Williams, Let’s Hear It For The Boy (1984)

“Shine On” from Dream On (1982)

“Diamonds” from Reach For It (1977)

“Canyon Lady” from Joe Henderson, Canyon Lady (1975)

“Foosh” from The Jean-Luc Ponty Experience With the George Duke Trio (1969)

“Soul Watcher” from Save the Country (1970)

“Heather” from Billy Cobham, Crosswinds (1974)

“You And Me” from From Me To You (1977)

“Look Into Her Eyes” from I Love The Blues, She Heard My Cry (1975)

“Open Your Eyes, You Can Fly” from Flora Purim, Open Your Eyes, You Can Fly (1976)

“Off the Wall” from Michael Jackson, Off the Wall (1979)

“Tryin’ and Cryin’” from Liberated Fantasies (1976)

“Every Little Step I Take” from Master of the Game (1979)

“Funny Funk” from Feel (1974)

“Dickie’s Such An Asshole” from Frank Zappa, live 12/10/73

“The Steam Drill” from Cannonball Adderley, The Black Messiah (1971)

“Reach For It” from Reach For It (1977)

“Dukey Stick” from Don’t Let Go (1978)

This is great (but the Apple Music link goes to a Dianne Reeves album?).