BRIEFS: Hip Hop's Multiple Deaths, The Return of Streaming Windows, and The Other Brats

Here's a new series where I blog about things that I find interesting in pop culture. Some of this will likely end up getting expanded.

Not Like Us?

Hip hop turned 50 last year, you might have heard. In its 51st year, Kendrick Lamar—hip hop’s closest thing to a revered, still-relevant spokesperson, his ties to West Side Pirus infinitely more relevant than his Pulitzer Prize—used Drake’s mixed race background, his Canadianness, and his alleged penchant for underaged women as a boxing speedbag. Lamar had already “he’s already dead!”ed Drake before his “Ken and Friends” Amazon livestream, but by all accounts, Lamar’s Inglewood-based spectacle of West Coast rap supremacy, which opened with “Euphoria” and ran “Not Like Us” back five times, drew to a massive conclusion, at least to one seasoned observer, “the best performance ever in a battle.”

As it happened, one of the most magical moments in hip-hop’s half-century history took place on a video livestream hosted by the world’s biggest online retailer on the same day that news broke that Verzuz—Timbaland and Swizz Beatz’ video “battle” platform for long-established rap stars—had signed a distribution deal with X, the platform owned by a white nationalist plutocrat. Verzuz, the entity that wondered, or maybe pleaded, “is hip hop back?” during the heat of the Kendrick/Drake beef has granted X the exclusive distribution rights to the programming that, in 2022, pulled in 5 million viewers across Instagram, Fite TV, Triller, YouTube, Facebook, Twitter and Twitch to watch Omarion compete in a sing-off against Mario. “We are beyond thrilled to have found the best partner for Verzuz,” Swizz told Billboard. “Not only are we excited to have Verzuz on X, we’re excited to help X build the biggest entertainment company in the world.”

Phew. The story reminded me that, pegged to last year’s golden anniversary, Jason England took to Defector to lament hip hop’s sad decline, citing old-school rappers’ collaborations with Tucker Carlson, Candace Owens and Joe Rogan, and new-schoolers’ lack of anything approaching a radical or even leftish political viewpoint to counter their elders’ raging conservatism:

And that brings us to the other major factor in hip hop’s death as a culture: It lost control of its own discourse, which guarantees incoherence and dilution. The tension between discourse and content—which plagues all art and media, all public intellectualism, and even the individual in ways most of us didn't foresee—has proven fatal. Expertise is de-incentivized: You don’t have to know what you’re talking about when the attention economy demands and rewards constant chatter.

As someone who wrote a whole book on the moment, right after the End of History, when a cohort of political rappers took temporary control of the national discourse on race in a forceful but also occasionally incoherent way until they were swallowed by the Spectacle, I took slight issue with England’s historical framing—”the attention economy” wasn’t invented by Twitter and Instagram but by ad-driven “platforms” like TV and radio—while smh’ing in solidarity with his point that current hip hop echoes the prosperity gospel of the modern megachurch more than the street reporting of its golden era.

Like rock before it, hip-hop is always dying, as England noted in his citations of 2004 Greg Tate and the intro to 1984’s foundational text Rap Attack. I’ll add Nelson George’s 1989 Voice column: “The farther the control of rap gets from its street corner constituency and the more corporations grasp it, the more vulnerable it becomes to cultural emasculation.” Tricia Rose would later lambaste George’s unchecked sexism with the whole “emasculation” thing, but this core point has been echoed down to England’s blog. Hip hop’s perennial zombie state makes for a tidy echo of Kevin Dettmar’s excellent point about critics lamenting rock’s so-called death(s), which, if you look back, was a discourse that emerged (like hip hop’s) more or less coterminous with its birth, bound up in legitimate but tired and unrecognized fears of Commercial Infiltration.

I wrote about it a bit here, but since the mid-1950s, rock’s infinite “rebirths” are a product of capitalism’s mandate of constant change, linked inextricably to youth culture’s fickle tastes. The same goes for hip hop—born from the idea that African-American youth deserved a piece of the so-called American Dream on their own terms—which served as the avant-garde for stylistic, technological, and yes, corporate innovation from the mid-1980s onward. On one hand, hip hop was a riposte to Reaganist law-and-order racism (ahem), while on the other, it was the quintessential artform of the neoliberal/postmodern era. The rules haven’t changed that much. The revolution will continue to be streamed.

In The Dealership, Trying To Get A Test Drive

Remember windowing? When huge artists like Adele declared that they wouldn’t simultaneously release their music to streaming services on release day, opting to drive fans toward the iTunes Music Store and Target to shell out for their new albums instead of listening for penny fractions on the dollar? “I believe music should be an event,” Adele told Time at the time. “It’s a bit disposable, streaming.” It’s back, but it’s not called windowing anymore. NxWorries just did the same thing with their new album, a tactic designed, per their manager, “to recreate the nostalgic feeling of truly appreciating the experience of a physical product that we all grew up with in the pre-streaming era.”

The strategy is certainly not new, but it went away when major labels decided instead that Hollywood-style “first week numbers” were the new way to introduce an album to the world, enrobed in digital data that recursively proved its worth. The strategy, whatever it’s called today, definitely works for artists who, in the post-iTunes Store era, can rely on a fanbase that still loves vinyl records (NxWorries is on Stones Throw, FWIW). That’s not everyone! But it’s definitely true for the Hoosier-connected International Anthem label, whose founder Scott McNiece is quoted in the piece. Yes, it’s about “physical media” and the importance of local record stores for McNiece, but it’s also about the crass basics of modern online commerce, aka the ability to generate two successive marketing campaigns—one for “physical” and one for streaming. If we’re not calling it “windowing” anymore, what other word works? I like “terracing,” but that’s why I’m not working in the record business.

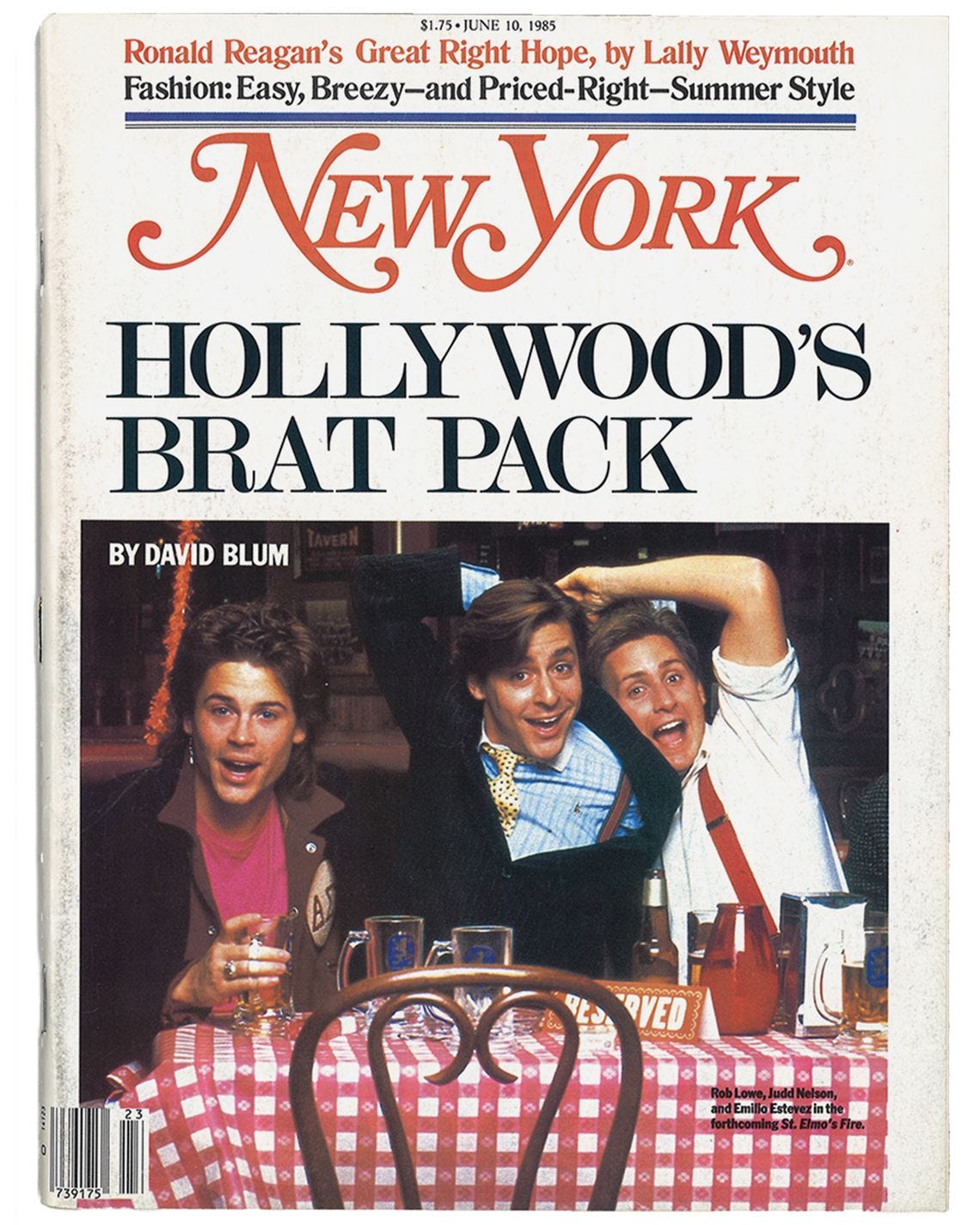

Not That BRAT, Those Brats

Because I’m 46, I put on Hulu’s BRATS documentary last night. I did so while paging through the original New York Magazine article that coined the wonderful phrase that Andrew McCarthy hates. And I realized that McCarthy himself is mentioned a total of one time in the article—which, the documentary explains, expanded from an initial profile of O.G. nepo baby Emilio Estevez. So while coinages like Brat Pack are definitionally nebulous, and of course McCarthy got roped into the discourse like Judd Nelson, Molly Ringwald, inter alia, there was still a bit of “out on the town having the time of my life with my fellow Brat Packers. They're all just out of frame, laughing too” to McCarthy’s attempt to come to terms with the term.

Of course, popular artists being lumped into a cutesy genre that develops a gravity of its own independent of their agency are well within their rights to resent it. And maybe some of these actors were denied roles because the word “brat” indicated they’d be childish divas on set. But it’s also the case that the early 80s young white actor gold rush was bound to wane after a few years, and we all know how nearly impossible it is to mature gracefully in Hollywood. But still: Emilio Estevez managed it through the mid-1990s, as did fellow Packers Demi Moore (who got Ghost after Ringwald turned it down?!), Rob Lowe, and Judd Nelson, and ancillary members like Jon Cryer, whose mercenary TV role-taking earned him the giant house that McCarthy interviews him inside during the documentary.

Nothing in Hollywood is monocausal any more than it is anywhere else, and it’s more than likely that McCarthy’s career took a Mannequin and Weekend At Bernie’s plunge not because producers were afraid to cast a member of the Brat Pack than about a billion other factors, including the likelihood that the man used up all of his swag in Pretty In Pink. He comes off in his self-directed documentary less as a 60-something Hollywood veteran curious to revisit his halcyon party days than as an unnecessarily entitled brat who makes Tucker Carlson faces at Malcolm Gladwell (yes, I chortled too when he popped up) because he didn’t get the long Hollywood career he somehow feels he deserved to have.

Not for nothing, two of McCarthy’s erstwhile contemporaries look amazing in this thing, and seem for all intents and purposes far more comfortable with the basic workings of a post-fame life than McCarthy: Ally Sheedy (my favorite BP’er) and especially Timothy Hutton, who is raising bees now.

The Funniest Thing I Read This Week:

…is TV writer and worthwhile Twitter presence Mike Drucker’s “I’m Personally Going To Force Game Companies To Put In All That Stuff You Hate.”

Why can’t we go back to the good old days of Metroid when you didn’t know you were playing as a woman until later? Back then, we didn’t have to have a character’s ‘whole identity’ crammed down our throats. Mainly because a character’s ‘whole identity’ was a four-by-ten stack of pixels. But now that games are more realistic, I’ve got a job to do, friendo. And that job is making sure that Lara Croft winks a little weird so she’s not sexy anymore. It’s almost like she can only wink by blinking. You’re turned off immediately. I bet you’re mad at that!

Have a good weekend.